#MeToo in Iran: Lessons & Questions Across Platforms

By Yasamin Rezaei

By Yasamin Rezaei

In a country like Iran, where streets have been taken away from people by the governmental force, and peaceful protests are responded to by armed police force, and in the time of enforced lockdowns during COVID-19, online activism is one of the most pressing areas in need of further research that humanities scholars must consider studying. Similar to the viral video of George Floyd’s murder by American police that led to the #BLM movement, no one knew a thunder leading to the ignition of #MeTooIran is on the way when a small multimedia news channel released a video interviewing female journalists on National Journalist’s day in Iran in August 2020.

This brief released documentary shared online portrayed a group of women journalists speaking out about their experiences of sexual assault at work. Studies surprisingly demonstrated that 90% of women in this occupation in Iran experience sexual harassment at least once in their career and 36% of these assaults come from top managers and politicians at news corporations or governmental institutions. The story, however, did not end with journalists.

#MeTooIran: How it began

Shortly after, a university student and survivor of sexual assault used Instagram to name her abuser. Mentioning “K.E.”, a former Art student of the University of Tehran initially named by his initials, launched a viral movement: more women with real names or anonymous accounts came forward to share their stories on Instagram and Twitter, many of them also naming “K.E.” This online movement, now called #MeTooIran or #من_هم led to a police investigation and the revelation that Keyvan Emamverdi had raped 300 women and more than 40 rape videos were found at his house.

“A serial rapist was discovered among stories on Instagram that led authorities to take action,” – says Elham Naeej, PhD in a webinar discussing #MeTooIran, the valuing of gendered violence, and the current status of online social activism in Alireza Ahmadian Lectures in Iranian and Persianate Studies. Presenting her research in the wake of the burgeoning “Me Too” movement in Iran, Naeej joined filmmakers Amin Pourbarghi and Ali Jenaban in discussing their documentary Hailstone’s Dance in January 2021. The short film about a girl who tells the story of her father’s domestic rape was analyzed to open an important talk about the legal shortcomings and socio-cultural impediments of rape culture and sexual assault in Iran. Victim blaming, the criminalization of same-sex relationships, obstacles to proving rape or sexual assault in court, the normalization of child marriage and marital rape through the law, taboos in the social discourse around sex, and valuing violence-based masculinity continue to be fundamental obstacles, according to Naeej.

This brief released documentary shared online portrayed a group of women journalists speaking out about their experiences of sexual assault at work. Studies surprisingly demonstrated that 90% of women in this occupation in Iran experience sexual harassment at least once in their career and 36% of these assaults come from top managers and politicians at news corporations or governmental institutions. The story, however, did not end with journalists.

#MeTooIran: How it began

Shortly after, a university student and survivor of sexual assault used Instagram to name her abuser. Mentioning “K.E.”, a former Art student of the University of Tehran initially named by his initials, launched a viral movement: more women with real names or anonymous accounts came forward to share their stories on Instagram and Twitter, many of them also naming “K.E.” This online movement, now called #MeTooIran or #من_هم led to a police investigation and the revelation that Keyvan Emamverdi had raped 300 women and more than 40 rape videos were found at his house. “A serial rapist was discovered among stories on Instagram that led authorities to take action,” – says Elham Naeej, PhD in a webinar discussing #MeTooIran, the valuing of gendered violence, and the current status of online social activism in Alireza Ahmadian Lectures in Iranian and Persianate Studies. Presenting her research in the wake of the burgeoning “Me Too” movement in Iran, Naeej joined filmmakers Amin Pourbarghi and Ali Jenaban in discussing their documentary Hailstone’s Dance in January 2021. The short film about a girl who tells the story of her father’s domestic rape was analyzed to open an important talk about the legal shortcomings and socio-cultural impediments of rape culture and sexual assault in Iran. Victim blaming, the criminalization of same-sex relationships, obstacles to proving rape or sexual assault in court, the normalization of child marriage and marital rape through the law, taboos in the social discourse around sex, and valuing violence-based masculinity continue to be fundamental obstacles, according to Naeej.

“A serial rapist was discovered among stories on Instagram that led authorities to take action,” – says Elham Naeej, PhD in a webinar discussing #MeTooIran, the valuing of gendered violence, and the current status of online social activism in Alireza Ahmadian Lectures in Iranian and Persianate Studies. Presenting her research in the wake of the burgeoning “Me Too” movement in Iran, Naeej joined filmmakers Amin Pourbarghi and Ali Jenaban in discussing their documentary Hailstone’s Dance in January 2021. The short film about a girl who tells the story of her father’s domestic rape was analyzed to open an important talk about the legal shortcomings and socio-cultural impediments of rape culture and sexual assault in Iran. Victim blaming, the criminalization of same-sex relationships, obstacles to proving rape or sexual assault in court, the normalization of child marriage and marital rape through the law, taboos in the social discourse around sex, and valuing violence-based masculinity continue to be fundamental obstacles, according to Naeej.

Although online platforms and digital activism are undermining the importance of geographical borders today more than ever, #MeToo is primarily known to be emerged on social media, connecting people from across the world through shared narratives in 2017 for the first time. The hashtag provided a virtual space for women and other survivors to share their stories. The magnitude of responses highlighted the prevalence of rape culture around the world and ushered in one of the first social media movements to have impacted society on a global scale.

Drawing on the mentioned Webinar, we will learn about #MeTooIran, the youngest resurgence of this movement, and its spread among Persian-speaking netizens inside and outside the country on different online social platforms. Then, we will ask how and why the scholars in Humanities should step in the discussions by raising, addressing, and exploring some crucial questions in the interdisciplinary field of social media studies.

Drawing on the mentioned Webinar, we will learn about #MeTooIran, the youngest resurgence of this movement, and its spread among Persian-speaking netizens inside and outside the country on different online social platforms. Then, we will ask how and why the scholars in Humanities should step in the discussions by raising, addressing, and exploring some crucial questions in the interdisciplinary field of social media studies.

How is #MeTooIran different?

Drawing some differences between #MeToo and #MeTooIran, Naeej states that after #MeToo in the West, there was a call for revisiting gender roles and the legal system while in Iran, there is still structural/cultural resistance to revisiting the legal system. “However, it led to online speaking outs and educational channels and regular and more widespread online activism.”, Naeej explains. “The rape narratives on digital platforms touched a sensitive point in society that empowered people to come forward. In some case, like Keyvan Emamverdi, a former archeology student who owned a bookshop near the University of Tehran, the narratives unprecedently led to legal actions.”

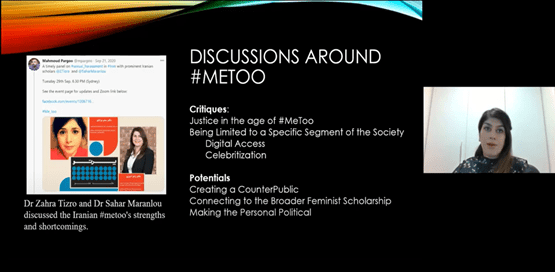

Celebrities, journalists, and politicians accused of sexual misconduct were forced to issue statements against accusations by netizens, in the absence of police intervention or investigation. Almost none of them, however, accepted or apologized. Social media netizens from different generations and backgrounds, from censored Facebook and Twitter to Instagram, were into this movement together, starting conversations online, and providing a platform for the narratives to be heard. According to Naeej, #MetooIran raised awareness about existing cultural and structural issues that prompted many panel discussions in which its strengths and shortcomings were discussed.

Naeej believes that the necessity of having digital access is one of the shortcomings of digital activism in Iran. Many victims do not have easy access to social media due to patriarchal and economic reasons. The privileging of certain narratives is also a concern: most center around artists and celebrities. Meanwhile, rape cases implicated in state-related segments of society perpetrated by politicians and government officials continue to be silenced as their participation in this digital movement might cause a threat to survivors.

This brief released documentary shared online portrayed a group of women journalists speaking out about their experiences of sexual assault at work. Studies surprisingly demonstrated that 90% of women in this occupation in Iran experience sexual harassment at least once in their career and 36% of these assaults come from top managers and politicians at news corporations or governmental institutions. The story, however, did not end with journalists.

#MeTooIran: How it began

Shortly after, a university student and survivor of sexual assault used Instagram to name her abuser. Mentioning “K.E.”, a former Art student of the University of Tehran initially named by his initials, launched a viral movement: more women with real names or anonymous accounts came forward to share their stories on Instagram and Twitter, many of them also naming “K.E.” This online movement, now called #MeTooIran or #من_هم led to a police investigation and the revelation that Keyvan Emamverdi had raped 300 women and more than 40 rape videos were found at his house.

“A serial rapist was discovered among stories on Instagram that led authorities to take action,” – says Elham Naeej, PhD in a webinar discussing #MeTooIran, the valuing of gendered violence, and the current status of online social activism in Alireza Ahmadian Lectures in Iranian and Persianate Studies. Presenting her research in the wake of the burgeoning “Me Too” movement in Iran, Naeej joined filmmakers Amin Pourbarghi and Ali Jenaban in discussing their documentary Hailstone’s Dance in January 2021. The short film about a girl who tells the story of her father’s domestic rape was analyzed to open an important talk about the legal shortcomings and socio-cultural impediments of rape culture and sexual assault in Iran. Victim blaming, the criminalization of same-sex relationships, obstacles to proving rape or sexual assault in court, the normalization of child marriage and marital rape through the law, taboos in the social discourse around sex, and valuing violence-based masculinity continue to be fundamental obstacles, according to Naeej.

Although online platforms and digital activism are undermining the importance of geographical borders today more than ever, #MeToo is primarily known to be emerged on social media, connecting people from across the world through shared narratives in 2017 for the first time. The hashtag provided a virtual space for women and other survivors to share their stories. The magnitude of responses highlighted the prevalence of rape culture around the world and ushered in one of the first social media movements to have impacted society on a global scale.

Drawing on the mentioned Webinar, we will learn about #MeTooIran, the youngest resurgence of this movement, and its spread among Persian-speaking netizens inside and outside the country on different online social platforms. Then, we will ask how and why the scholars in Humanities should step in the discussions by raising, addressing, and exploring some crucial questions in the interdisciplinary field of social media studies.

Drawing on the mentioned Webinar, we will learn about #MeTooIran, the youngest resurgence of this movement, and its spread among Persian-speaking netizens inside and outside the country on different online social platforms. Then, we will ask how and why the scholars in Humanities should step in the discussions by raising, addressing, and exploring some crucial questions in the interdisciplinary field of social media studies.

How is #MeTooIran different?

Drawing some differences between #MeToo and #MeTooIran, Naeej states that after #MeToo in the West, there was a call for revisiting gender roles and the legal system while in Iran, there is still structural/cultural resistance to revisiting the legal system. “However, it led to online speaking outs and educational channels and regular and more widespread online activism.”, Naeej explains. “The rape narratives on digital platforms touched a sensitive point in society that empowered people to come forward. In some case, like Keyvan Emamverdi, a former archeology student who owned a bookshop near the University of Tehran, the narratives unprecedently led to legal actions.”

Celebrities, journalists, and politicians accused of sexual misconduct were forced to issue statements against accusations by netizens, in the absence of police intervention or investigation. Almost none of them, however, accepted or apologized. Social media netizens from different generations and backgrounds, from censored Facebook and Twitter to Instagram, were into this movement together, starting conversations online, and providing a platform for the narratives to be heard. According to Naeej, #MetooIran raised awareness about existing cultural and structural issues that prompted many panel discussions in which its strengths and shortcomings were discussed.

Naeej believes that the necessity of having digital access is one of the shortcomings of digital activism in Iran. Many victims do not have easy access to social media due to patriarchal and economic reasons. The privileging of certain narratives is also a concern: most center around artists and celebrities. Meanwhile, rape cases implicated in state-related segments of society perpetrated by politicians and government officials continue to be silenced as their participation in this digital movement might cause a threat to survivors.

Although online platforms and digital activism are undermining the importance of geographical borders today more than ever, #MeToo is primarily known to be emerged on social media, connecting people from across the world through shared narratives in 2017 for the first time. The hashtag provided a virtual space for women and other survivors to share their stories. The magnitude of responses highlighted the prevalence of rape culture around the world and ushered in one of the first social media movements to have impacted society on a global scale.

Drawing on the mentioned Webinar, we will learn about #MeTooIran, the youngest resurgence of this movement, and its spread among Persian-speaking netizens inside and outside the country on different online social platforms. Then, we will ask how and why the scholars in Humanities should step in the discussions by raising, addressing, and exploring some crucial questions in the interdisciplinary field of social media studies.

Drawing on the mentioned Webinar, we will learn about #MeTooIran, the youngest resurgence of this movement, and its spread among Persian-speaking netizens inside and outside the country on different online social platforms. Then, we will ask how and why the scholars in Humanities should step in the discussions by raising, addressing, and exploring some crucial questions in the interdisciplinary field of social media studies.

How is #MeTooIran different?

Drawing some differences between #MeToo and #MeTooIran, Naeej states that after #MeToo in the West, there was a call for revisiting gender roles and the legal system while in Iran, there is still structural/cultural resistance to revisiting the legal system. “However, it led to online speaking outs and educational channels and regular and more widespread online activism.”, Naeej explains. “The rape narratives on digital platforms touched a sensitive point in society that empowered people to come forward. In some case, like Keyvan Emamverdi, a former archeology student who owned a bookshop near the University of Tehran, the narratives unprecedently led to legal actions.”

Celebrities, journalists, and politicians accused of sexual misconduct were forced to issue statements against accusations by netizens, in the absence of police intervention or investigation. Almost none of them, however, accepted or apologized. Social media netizens from different generations and backgrounds, from censored Facebook and Twitter to Instagram, were into this movement together, starting conversations online, and providing a platform for the narratives to be heard. According to Naeej, #MetooIran raised awareness about existing cultural and structural issues that prompted many panel discussions in which its strengths and shortcomings were discussed.

Naeej believes that the necessity of having digital access is one of the shortcomings of digital activism in Iran. Many victims do not have easy access to social media due to patriarchal and economic reasons. The privileging of certain narratives is also a concern: most center around artists and celebrities. Meanwhile, rape cases implicated in state-related segments of society perpetrated by politicians and government officials continue to be silenced as their participation in this digital movement might cause a threat to survivors.

The benefits, according to Naeej, have nevertheless been valuable enough for this movement to emerge and progress. For once, talking about rape was not scolded and did not reproduce rape culture but initiated discussions against hegemonic discourses. Activism and mostly feminists moved to social media, where they have a platform with no censor. In the closed political atmosphere of today’s Iran, a degree of democracy or political freedom was practiced. Naeej ended the presentation by stating: “Women said what neither patriarchal society nor the regime wanted to hear and became dangerous: Personal narratives became performative social acts.” The webinar ended by a noteworthy acknowledgement that long before hashtags , journalist Masih Alinejad started a feminist digital activist campaign in 2012 called Stealthy Freedom, which gave women a platform to post photos of themselves on the streets of Iran without veils to protest against compulsory Hijab-wearing. Alinejad deserves more attention in studies of digital activism in Iran.

What was missing in this talk?

Although the webinar raised many essential points in counting the social benefits and shortcomings of #MeTooIran, there was – and still, there is- more scope to delve into the discussion of how marginalized people of the LGBTQi+ community found a platform through this hashtag to share their narratives of rape, too, disclosing many severe cultural issues that this community in Iran is facing with.

Naeej pointed out to #از_سربازی_بگو, translated to “tell me about military service,” under which shocking narratives about rape and rape culture in the military were revealed online. Born under the umbrella of #MeTooIran and condemning compulsory military service in Iran, this hashtag did not receive as much attention it deserved. Most of the narrators tweeted by anonymous accounts due to the social pressure of Iran’s society. Narrations by men who were sexually abused at single-sex schools were also spread at the same time and disappeared shortly after a while.

Platform matters: Women used Clubhouse to turn the table

Since the #MeToo and the Valuing the (Gendered) Violence in Iran’s webinar in January 2021 until now, the #MeTooIran has tremendously evolved. It is now hard to ignore that one of the boldest cases of online activism that led to weeks of regular online presence of netizens under this hashtag, is Mohsen Namjoo‘s, an Iranian New York-based superstar dubbed the Bob Dylan of Iran, who faced multiple allegations of sexual misconduct. After rumors spread on Twitter in the summer of 2020, he released a video message denying the allegations. His accusers protested further, however, after the superstar appeared in a Persian New Year’s music show in March 2021. Amid the war of platforms, female artists and social media activists harshly condemned the Persian media abroad for unfairly supporting male artists under every circumstance. They believed in a time when the ban on Iranian women’s voice in the music industry has obliged many Iranian female singers to immigrate to keep their singing career, hoping to rely on Persian Mass media channels abroad; these channels have been supporting male artists in many ways. Ignoring the voices of women who these male artists have sexually assaulted was told to be one of them.

The benefits, according to Naeej, have nevertheless been valuable enough for this movement to emerge and progress. For once, talking about rape was not scolded and did not reproduce rape culture but initiated discussions against hegemonic discourses. Activism and mostly feminists moved to social media, where they have a platform with no censor. In the closed political atmosphere of today’s Iran, a degree of democracy or political freedom was practiced. Naeej ended the presentation by stating: “Women said what neither patriarchal society nor the regime wanted to hear and became dangerous: Personal narratives became performative social acts.” The webinar ended by a noteworthy acknowledgement that long before hashtags , journalist Masih Alinejad started a feminist digital activist campaign in 2012 called Stealthy Freedom, which gave women a platform to post photos of themselves on the streets of Iran without veils to protest against compulsory Hijab-wearing. Alinejad deserves more attention in studies of digital activism in Iran.

What was missing in this talk?

Although the webinar raised many essential points in counting the social benefits and shortcomings of #MeTooIran, there was – and still, there is- more scope to delve into the discussion of how marginalized people of the LGBTQi+ community found a platform through this hashtag to share their narratives of rape, too, disclosing many severe cultural issues that this community in Iran is facing with.

Naeej pointed out to #از_سربازی_بگو, translated to “tell me about military service,” under which shocking narratives about rape and rape culture in the military were revealed online. Born under the umbrella of #MeTooIran and condemning compulsory military service in Iran, this hashtag did not receive as much attention it deserved. Most of the narrators tweeted by anonymous accounts due to the social pressure of Iran’s society. Narrations by men who were sexually abused at single-sex schools were also spread at the same time and disappeared shortly after a while.

Platform matters: Women used Clubhouse to turn the table

Since the #MeToo and the Valuing the (Gendered) Violence in Iran’s webinar in January 2021 until now, the #MeTooIran has tremendously evolved. It is now hard to ignore that one of the boldest cases of online activism that led to weeks of regular online presence of netizens under this hashtag, is Mohsen Namjoo‘s, an Iranian New York-based superstar dubbed the Bob Dylan of Iran, who faced multiple allegations of sexual misconduct. After rumors spread on Twitter in the summer of 2020, he released a video message denying the allegations. His accusers protested further, however, after the superstar appeared in a Persian New Year’s music show in March 2021. Amid the war of platforms, female artists and social media activists harshly condemned the Persian media abroad for unfairly supporting male artists under every circumstance. They believed in a time when the ban on Iranian women’s voice in the music industry has obliged many Iranian female singers to immigrate to keep their singing career, hoping to rely on Persian Mass media channels abroad; these channels have been supporting male artists in many ways. Ignoring the voices of women who these male artists have sexually assaulted was told to be one of them.

The benefits, according to Naeej, have nevertheless been valuable enough for this movement to emerge and progress. For once, talking about rape was not scolded and did not reproduce rape culture but initiated discussions against hegemonic discourses. Activism and mostly feminists moved to social media, where they have a platform with no censor. In the closed political atmosphere of today’s Iran, a degree of democracy or political freedom was practiced. Naeej ended the presentation by stating: “Women said what neither patriarchal society nor the regime wanted to hear and became dangerous: Personal narratives became performative social acts.” The webinar ended by a noteworthy acknowledgement that long before hashtags , journalist Masih Alinejad started a feminist digital activist campaign in 2012 called Stealthy Freedom, which gave women a platform to post photos of themselves on the streets of Iran without veils to protest against compulsory Hijab-wearing. Alinejad deserves more attention in studies of digital activism in Iran.

What was missing in this talk?

Although the webinar raised many essential points in counting the social benefits and shortcomings of #MeTooIran, there was – and still, there is- more scope to delve into the discussion of how marginalized people of the LGBTQi+ community found a platform through this hashtag to share their narratives of rape, too, disclosing many severe cultural issues that this community in Iran is facing with.

Naeej pointed out to #از_سربازی_بگو, translated to “tell me about military service,” under which shocking narratives about rape and rape culture in the military were revealed online. Born under the umbrella of #MeTooIran and condemning compulsory military service in Iran, this hashtag did not receive as much attention it deserved. Most of the narrators tweeted by anonymous accounts due to the social pressure of Iran’s society. Narrations by men who were sexually abused at single-sex schools were also spread at the same time and disappeared shortly after a while.

Platform matters: Women used Clubhouse to turn the table

Since the #MeToo and the Valuing the (Gendered) Violence in Iran’s webinar in January 2021 until now, the #MeTooIran has tremendously evolved. It is now hard to ignore that one of the boldest cases of online activism that led to weeks of regular online presence of netizens under this hashtag, is Mohsen Namjoo‘s, an Iranian New York-based superstar dubbed the Bob Dylan of Iran, who faced multiple allegations of sexual misconduct. After rumors spread on Twitter in the summer of 2020, he released a video message denying the allegations. His accusers protested further, however, after the superstar appeared in a Persian New Year’s music show in March 2021. Amid the war of platforms, female artists and social media activists harshly condemned the Persian media abroad for unfairly supporting male artists under every circumstance. They believed in a time when the ban on Iranian women’s voice in the music industry has obliged many Iranian female singers to immigrate to keep their singing career, hoping to rely on Persian Mass media channels abroad; these channels have been supporting male artists in many ways. Ignoring the voices of women who these male artists have sexually assaulted was told to be one of them.

Starting on ClubHouse, a live stream audio-sharing app that allows users to speak and debate in different audio chatrooms, discussions around sexual misconduct of Namjoo gained momentum. The urgency of the debate and the popularity of mentioned artist attracted thousands of people, including well-known journalists, politicians, and actors from both inside and outside of Iran. For the first time in the brief history of digital activism in Iran, the voice of the unheard, in its literal meaning, was not given but achieved by marginalized groups such as women. Victim-blaming, patriarchy, and gendered culture were harshly condemned and widely analyzed. Women and the LGBTQi+ community found a platform that allowed them to share more than only photos and captions. The medium turned to the message itself, saying: “Listen to us and talk to us. We’re more than avatars and cyber pages you might not ‘like’ and scroll down.”

Starting on ClubHouse, a live stream audio-sharing app that allows users to speak and debate in different audio chatrooms, discussions around sexual misconduct of Namjoo gained momentum. The urgency of the debate and the popularity of mentioned artist attracted thousands of people, including well-known journalists, politicians, and actors from both inside and outside of Iran. For the first time in the brief history of digital activism in Iran, the voice of the unheard, in its literal meaning, was not given but achieved by marginalized groups such as women. Victim-blaming, patriarchy, and gendered culture were harshly condemned and widely analyzed. Women and the LGBTQi+ community found a platform that allowed them to share more than only photos and captions. The medium turned to the message itself, saying: “Listen to us and talk to us. We’re more than avatars and cyber pages you might not ‘like’ and scroll down.”

On Clubhouse, voices took a step back from embodied genders and gendered bodies. In a newly-created intimate atmosphere, these voices narrated stories and appeared as independent identities. The identities that have been easily suppressed and censored from authorities, culture, and mass media in Iran for long, such as sexually harassed women, homosexuals, transwomen, transmen, and queer identities, were heard as audio metadata detached from their bodies. The bodies that had turned to a symbol of an anomaly in a society long suppressed by taboos and controlled by so-called Islamic ideologies from schools to homes and the media. #MeTooIran ignited on Youtube and Instagram, born on Twitter and spread out through Instagram, has now moved to a new platform: an only-audio-sharing app, evolving and carrying the same message. This is the interesting feature of digital activism: most of them are fluid enough to take up space from one platform to another. The message embraces the medium, and the medium embraces the message. This constantly-changing relationship is worth exploring, while the cultural outputs are hard to ignore.

Keeping up with young online movements: #MeTooIran needs rapid deep exploration

Many questions in social media and internet studies should be explored in light of #MeTooIran: Why and how do the online platforms hosting this movement matter? What has changed and been challenged by this digital activism in society, and how is it influencing and reshaping users’ online behavior? How have the online platforms been used to shape the vocabulary of discourses around sexual abuse and rape culture in the real world outside of online platforms, in a country like Iran, where legal institutions and the law appear to be inefficient and incomplete? And most importantly, Where does the intersection of new emerging media studies, feminist discourse, pop culture, and celebrity studies stand in raising these questions?

On the other hand, how digital platforms like Twitter, Instagram, or Clubhouse have instigated these taboo discussions around sexual abuse despite the presence of cultural barriers, the ones that make the talk about sexual abuse in the real world over the physical presence of people impossible, tells us that the medium is the message if it is not more powerful than it. The sort of intimacy these platforms have created or how they detach the individuality and the real identity of narrators from their narratives have resulted in creating a safer space for survivors to open up. This space has not always been safe. The non-stop attempt of activists on Instagram, Twitter, and ClubHouse has made it happen.

On the other hand, how digital platforms like Twitter, Instagram, or Clubhouse have instigated these taboo discussions around sexual abuse despite the presence of cultural barriers, the ones that make the talk about sexual abuse in the real world over the physical presence of people impossible, tells us that the medium is the message if it is not more powerful than it. The sort of intimacy these platforms have created or how they detach the individuality and the real identity of narrators from their narratives have resulted in creating a safer space for survivors to open up. This space has not always been safe. The non-stop attempt of activists on Instagram, Twitter, and ClubHouse has made it happen.

Another question to explore might be: what separates fact-based and powerful mass media and traditional journalism from social media accounts? It is hard to ignore that #MeToo has been born and raised on social media; mass media and professional journalism has not contributed to its development—which is one of the main critiques this movement had toward them as keeping their place as a hegemony of power, supporting sexual abusers in powerful positions of society.

Interestingly enough, as long as the people, especially those in power, accused of sexual misconduct online, are denied participating in the happenings and conversations on these platforms by looking down on social media and underestimating it, the battles are lost in favor of digital activists. Regardless of the power and its influence, underestimating online activism and understudying online platforms and their essence in countries with limited freedom of speech or the flawed legal system will have consequences in the long term. Online platforms have challenged the old game of power vs. influence, and more changes are on the way.

Starting on ClubHouse, a live stream audio-sharing app that allows users to speak and debate in different audio chatrooms, discussions around sexual misconduct of Namjoo gained momentum. The urgency of the debate and the popularity of mentioned artist attracted thousands of people, including well-known journalists, politicians, and actors from both inside and outside of Iran. For the first time in the brief history of digital activism in Iran, the voice of the unheard, in its literal meaning, was not given but achieved by marginalized groups such as women. Victim-blaming, patriarchy, and gendered culture were harshly condemned and widely analyzed. Women and the LGBTQi+ community found a platform that allowed them to share more than only photos and captions. The medium turned to the message itself, saying: “Listen to us and talk to us. We’re more than avatars and cyber pages you might not ‘like’ and scroll down.”

Starting on ClubHouse, a live stream audio-sharing app that allows users to speak and debate in different audio chatrooms, discussions around sexual misconduct of Namjoo gained momentum. The urgency of the debate and the popularity of mentioned artist attracted thousands of people, including well-known journalists, politicians, and actors from both inside and outside of Iran. For the first time in the brief history of digital activism in Iran, the voice of the unheard, in its literal meaning, was not given but achieved by marginalized groups such as women. Victim-blaming, patriarchy, and gendered culture were harshly condemned and widely analyzed. Women and the LGBTQi+ community found a platform that allowed them to share more than only photos and captions. The medium turned to the message itself, saying: “Listen to us and talk to us. We’re more than avatars and cyber pages you might not ‘like’ and scroll down.”

On Clubhouse, voices took a step back from embodied genders and gendered bodies. In a newly-created intimate atmosphere, these voices narrated stories and appeared as independent identities. The identities that have been easily suppressed and censored from authorities, culture, and mass media in Iran for long, such as sexually harassed women, homosexuals, transwomen, transmen, and queer identities, were heard as audio metadata detached from their bodies. The bodies that had turned to a symbol of an anomaly in a society long suppressed by taboos and controlled by so-called Islamic ideologies from schools to homes and the media. #MeTooIran ignited on Youtube and Instagram, born on Twitter and spread out through Instagram, has now moved to a new platform: an only-audio-sharing app, evolving and carrying the same message. This is the interesting feature of digital activism: most of them are fluid enough to take up space from one platform to another. The message embraces the medium, and the medium embraces the message. This constantly-changing relationship is worth exploring, while the cultural outputs are hard to ignore.

Keeping up with young online movements: #MeTooIran needs rapid deep exploration

Many questions in social media and internet studies should be explored in light of #MeTooIran: Why and how do the online platforms hosting this movement matter? What has changed and been challenged by this digital activism in society, and how is it influencing and reshaping users’ online behavior? How have the online platforms been used to shape the vocabulary of discourses around sexual abuse and rape culture in the real world outside of online platforms, in a country like Iran, where legal institutions and the law appear to be inefficient and incomplete? And most importantly, Where does the intersection of new emerging media studies, feminist discourse, pop culture, and celebrity studies stand in raising these questions?

On the other hand, how digital platforms like Twitter, Instagram, or Clubhouse have instigated these taboo discussions around sexual abuse despite the presence of cultural barriers, the ones that make the talk about sexual abuse in the real world over the physical presence of people impossible, tells us that the medium is the message if it is not more powerful than it. The sort of intimacy these platforms have created or how they detach the individuality and the real identity of narrators from their narratives have resulted in creating a safer space for survivors to open up. This space has not always been safe. The non-stop attempt of activists on Instagram, Twitter, and ClubHouse has made it happen.

On the other hand, how digital platforms like Twitter, Instagram, or Clubhouse have instigated these taboo discussions around sexual abuse despite the presence of cultural barriers, the ones that make the talk about sexual abuse in the real world over the physical presence of people impossible, tells us that the medium is the message if it is not more powerful than it. The sort of intimacy these platforms have created or how they detach the individuality and the real identity of narrators from their narratives have resulted in creating a safer space for survivors to open up. This space has not always been safe. The non-stop attempt of activists on Instagram, Twitter, and ClubHouse has made it happen.

Another question to explore might be: what separates fact-based and powerful mass media and traditional journalism from social media accounts? It is hard to ignore that #MeToo has been born and raised on social media; mass media and professional journalism has not contributed to its development—which is one of the main critiques this movement had toward them as keeping their place as a hegemony of power, supporting sexual abusers in powerful positions of society.

Interestingly enough, as long as the people, especially those in power, accused of sexual misconduct online, are denied participating in the happenings and conversations on these platforms by looking down on social media and underestimating it, the battles are lost in favor of digital activists. Regardless of the power and its influence, underestimating online activism and understudying online platforms and their essence in countries with limited freedom of speech or the flawed legal system will have consequences in the long term. Online platforms have challenged the old game of power vs. influence, and more changes are on the way.

Starting on ClubHouse, a live stream audio-sharing app that allows users to speak and debate in different audio chatrooms, discussions around sexual misconduct of Namjoo gained momentum. The urgency of the debate and the popularity of mentioned artist attracted thousands of people, including well-known journalists, politicians, and actors from both inside and outside of Iran. For the first time in the brief history of digital activism in Iran, the voice of the unheard, in its literal meaning, was not given but achieved by marginalized groups such as women. Victim-blaming, patriarchy, and gendered culture were harshly condemned and widely analyzed. Women and the LGBTQi+ community found a platform that allowed them to share more than only photos and captions. The medium turned to the message itself, saying: “Listen to us and talk to us. We’re more than avatars and cyber pages you might not ‘like’ and scroll down.”

Starting on ClubHouse, a live stream audio-sharing app that allows users to speak and debate in different audio chatrooms, discussions around sexual misconduct of Namjoo gained momentum. The urgency of the debate and the popularity of mentioned artist attracted thousands of people, including well-known journalists, politicians, and actors from both inside and outside of Iran. For the first time in the brief history of digital activism in Iran, the voice of the unheard, in its literal meaning, was not given but achieved by marginalized groups such as women. Victim-blaming, patriarchy, and gendered culture were harshly condemned and widely analyzed. Women and the LGBTQi+ community found a platform that allowed them to share more than only photos and captions. The medium turned to the message itself, saying: “Listen to us and talk to us. We’re more than avatars and cyber pages you might not ‘like’ and scroll down.”

On Clubhouse, voices took a step back from embodied genders and gendered bodies. In a newly-created intimate atmosphere, these voices narrated stories and appeared as independent identities. The identities that have been easily suppressed and censored from authorities, culture, and mass media in Iran for long, such as sexually harassed women, homosexuals, transwomen, transmen, and queer identities, were heard as audio metadata detached from their bodies. The bodies that had turned to a symbol of an anomaly in a society long suppressed by taboos and controlled by so-called Islamic ideologies from schools to homes and the media. #MeTooIran ignited on Youtube and Instagram, born on Twitter and spread out through Instagram, has now moved to a new platform: an only-audio-sharing app, evolving and carrying the same message. This is the interesting feature of digital activism: most of them are fluid enough to take up space from one platform to another. The message embraces the medium, and the medium embraces the message. This constantly-changing relationship is worth exploring, while the cultural outputs are hard to ignore.

Keeping up with young online movements: #MeTooIran needs rapid deep exploration

Many questions in social media and internet studies should be explored in light of #MeTooIran: Why and how do the online platforms hosting this movement matter? What has changed and been challenged by this digital activism in society, and how is it influencing and reshaping users’ online behavior? How have the online platforms been used to shape the vocabulary of discourses around sexual abuse and rape culture in the real world outside of online platforms, in a country like Iran, where legal institutions and the law appear to be inefficient and incomplete? And most importantly, Where does the intersection of new emerging media studies, feminist discourse, pop culture, and celebrity studies stand in raising these questions?

On the other hand, how digital platforms like Twitter, Instagram, or Clubhouse have instigated these taboo discussions around sexual abuse despite the presence of cultural barriers, the ones that make the talk about sexual abuse in the real world over the physical presence of people impossible, tells us that the medium is the message if it is not more powerful than it. The sort of intimacy these platforms have created or how they detach the individuality and the real identity of narrators from their narratives have resulted in creating a safer space for survivors to open up. This space has not always been safe. The non-stop attempt of activists on Instagram, Twitter, and ClubHouse has made it happen.

On the other hand, how digital platforms like Twitter, Instagram, or Clubhouse have instigated these taboo discussions around sexual abuse despite the presence of cultural barriers, the ones that make the talk about sexual abuse in the real world over the physical presence of people impossible, tells us that the medium is the message if it is not more powerful than it. The sort of intimacy these platforms have created or how they detach the individuality and the real identity of narrators from their narratives have resulted in creating a safer space for survivors to open up. This space has not always been safe. The non-stop attempt of activists on Instagram, Twitter, and ClubHouse has made it happen.

Another question to explore might be: what separates fact-based and powerful mass media and traditional journalism from social media accounts? It is hard to ignore that #MeToo has been born and raised on social media; mass media and professional journalism has not contributed to its development—which is one of the main critiques this movement had toward them as keeping their place as a hegemony of power, supporting sexual abusers in powerful positions of society.

Interestingly enough, as long as the people, especially those in power, accused of sexual misconduct online, are denied participating in the happenings and conversations on these platforms by looking down on social media and underestimating it, the battles are lost in favor of digital activists. Regardless of the power and its influence, underestimating online activism and understudying online platforms and their essence in countries with limited freedom of speech or the flawed legal system will have consequences in the long term. Online platforms have challenged the old game of power vs. influence, and more changes are on the way.